The park is both blank canvas and actualized aesthetic vision. As a setting—blank canvas—it provides infinite opportunity for activity. Think of a grass patch as a stage and cartwheels as a performance and the spectators on a nearby picnic blanket are their own plein-air theatrical expression, the adjacent play equipment harbors a gymnastic drama acted out by children. We place the blanket on the grass with the eye of an artist, we lay ourselves out on it and position ourselves, crooked elbow propping our head as we lazily eat an apple, models for the unacknowledged and imaginary portrait that develops as a nearly propagandistic advertisement for the culture that creates and inhabits the park. Some denizens of the park actually sit and draw what transpires and yet always is around them, some with guitars sing songs that express both the park and themselves as they perceive it. Picnic fare is pulled from bags and eaten, again both the movie theater snack of the observer acquired in the lobby of the-world-outside-the-park and the subject of the whole experience. The park is a movie theater in which the screen is replaced by more seats, the lights are on, and its visitors consume the images of each other, some reading, some napping, some playing, some simply snacking on popcorn and lazily scanning the setting, following the arc of the ball with our eyes, the gentle necking of the young lovers.

The park is already a completed work of art before its invisible gates are opened by the dawn and the actors of the world are invited in. Its architect envisioned the taming and sculpting of a collection of acres, and its landscapers molded it to the intended hues and dimensions. And so we walk the ordered and beautiful paths of the Palacio de Generalife as aficionados stroll through the corridors of an art museum, appreciating the work, the history, the moment of the masterpiece’s transition through the stages of nature, each tree a reincarnation of the very bristles used by the artist centuries previous. We are not at ease, however, as we might be in a public park, we are not creative—and not just because we paid an admittance fee—because we are shuffled along through a predetermined experience of the park, it is not even a park now, it is too much art. It is Disneyland, it is the setting defining the experience, you are a spectator to yourself on the canvas as you are at the movie theater, in a dream state, your own subconscious reflected back at you through a series of pre-determined images, the mass-production of experience.

The park is a paint-by-numbers, it is incomplete until human life animates it, fleshes out the pre-determined greens. It is total nature and without art until the perception of it by somebody awakens it, uses its path, runs fingers over the bark of the trees and acknowledges the harmony between man and nature, perception and interaction creating the fluid tapestry that is the unfinished though always complete canvas of the park.

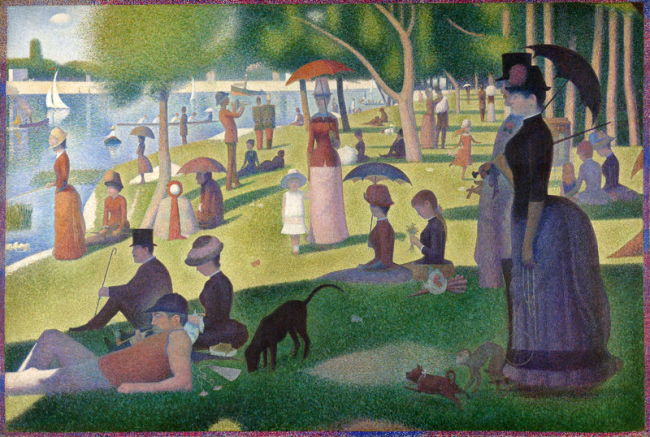

Think of Seurat’s Un dimanche après-midi à l’Île de la Grande Jatte.

The image develops as a synthesis of the setting and the denizens of the park, an island in this case just outside Paris on the Seine, which would be plain without the people. The painting uses the lawn and the river as the verdant and azure canvas on which Seurat expresses his view of society, and the diversity of parisian identity is held in the mirror of the river and in turn reflected in the implied activity of the plein-air painter, and its subjects sit and contemplate it themselves, or stroll through it in the shade of their parasols, or glide by in their rowboats or sailboats. It is Sunday after all and the sun is out shining upon a world that awaits us, that invites the brushstrokes of our interaction, all of us, top-hatted or short-sleeved, lounging or rowing, dog or monkey, and is that a policeman or a mime? There’s always room for interpretation. That’s what the open invitation to the park is all about.