Last month I moved back into my parents’ house after six-odd months of traveling and not making money in order to do the opposite of those things (staying in one spot and making money). However, my parents live—where I grew up—in an area of Monterey County where the bus runs once a day, referred to as The Pastures of Heaven in Steinbeck’s work of the same name; and I don’t have a car. While it is a meager ten-minute drive to Salinas and I have a more-than-competent road bicycle, to say the route is not bike friendly is a severe understatement. To cross the Salinas River one must merge onto Highway 68, a two-lane freeway in this interval, and then navigate farm roads whose shoulder may be described as the confluence of dirt debris from the field drug out by tractors and the pebbles, trash and everything else that cars push to the side of the road.

The day before my first day back substitute teaching in East Salinas I looked at google maps to confirm that commuting by bicycle was essentially untenable as an option, and indeed, the 68 bridge was the only crossing for miles; Davis Road, to the North, is the only other way which would drop me off on the wrong side of Salinas, adding at least a half hour to my trip. I did notice something unexpected: just north of the freeway bridge was a green patch labeled with the little evergreen icon that signifies the great respite from commerce, civilization and all genres of day-to-day hustle: the park. It was labelled Hilltown Ferry State Historic Landmark. This was strange for a number of reasons:

1. I grew up here and lived here half of my adult life as well and had never heard of it, there is no signage, etc.

2. To the best of my knowledge the green of this map corresponded to an overgrown and inaccessible patch of land.

3. The notion of “Historic Landmark” seemed the opposite of everything this place was in my mind.

In other words, the section of the Salinas River just north of Highway 68 that I had driven by thousands of times was an historical site mentioned in the same list as the California missions, the building in which the California Constitution was drafted and signed (NO. 126 COLTON HALL), the site of Sutter’s Mill where gold was discovered on January 24, 1848 (NO. 530), and the site of the Brian, Dennis and Carl Wilson’s childhood home, where the Beach Boys formed and made their first recordings (NO. 1041 [seriously, quoting the Office of Historic Preservation: “The music of the Beach Boys broadcast to the world an image of California as a place of sun, surf, and romance.” This is what passes for history in California]). I didn’t think much more of it and, instead, called a family friend who teaches first grade and asked if I could carpool with her the next day and she agreed, meeting me at an intersection just this side of the river. I locked my bike for the day at an unmarked faux-adobe, strip-mall-style (one-story) office building’s unused bike rack, a bizarre concession to a bike-riding population that, beyond my present use, does not exist (with the exception, of course, of people driving bikes in tow to the Creekside entrance to Fort Ord for to mountain bike. I was a little nervous leaving my bike in a place whose only signage warned me not to trespass, but, I felt even more uncomfortable going into an office that didn’t announce its purpose at its threshold and, at 7:15, there was no one there anyway.

When she pulled up I told her about my predicament first—”oh, you mean the Bridge of Death,” she said after we crossed over it—and then the historic landmark, which she had never heard of either. When I was dropped back at the unidentified office building at the end of the day my bike was still there, though it had been knocked over by, I’d like to think, the wind.

The California State Parks Office of Historic Preservation’s website describes Landmark NO. 56O HILL TOWN FERRY like this:

Operated by Hiram Cory, this was one of the first ferries to cross the Salinas River. The Monterey County Board of Supervisors regulated the toll which was, in 1877: buggy and horse, 25 cents, buggy and horses, 37-1/2 cents, four horses and wagon, 85 cents, six horses and wagon, $1, horse and saddle, 25 cents, and man on foot, 12-1/2 cents. The ferry operated until a bridge was built in 1889.

What is at stake here seems more conceptual—if something were to be preserved it would be the craft that shuttled people across the river, the landing platforms on either side, or the apparatus that suspended the rope that guided the ferry. Instead it is the site where, by a kind of magic someone like me in the 21st century couldn’t understand, commuters of the pioneer age were spirited over water and on their way. In a sense the freeway that passes over the natural ford in the river is the landmark, transporting commuters 20 feet above the site where Juan Bautista de Anza and his men crossed back in 1776, a modern day viewing platform that its users don’t actually realize reveals anything meaningful and speed over at 70 miles an hour.

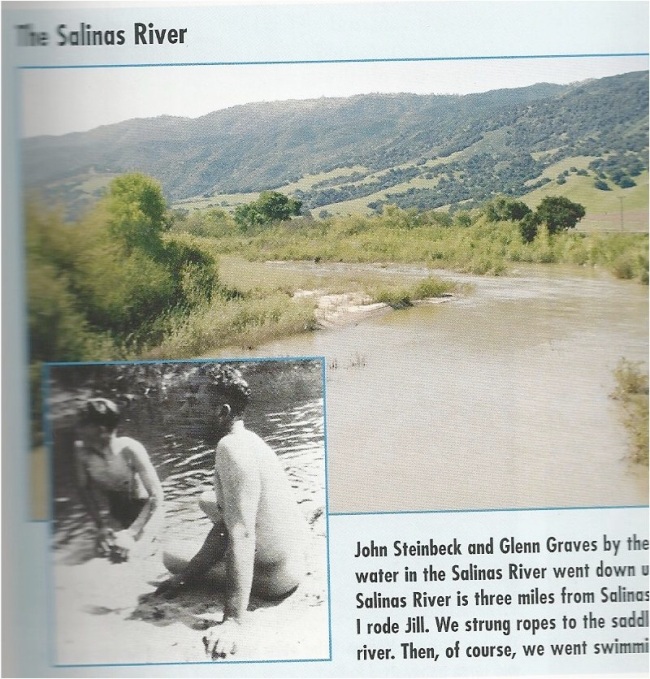

As someone who grew up a few miles from the Salinas River and along the El Toro Creek, the last tributary descending from the Santa Lucia Range, I never really thought about the Salinas as a waterway to be crossed, with the exception of the 1994 el niño winter rains that caused the normally piddly stream to top the 68 bridge canceling school for a few days. It is a river that flows one week a year is completely dry six months, “a part-time river,” in the words of John Steinbeck, an “upside-down river” in the title of a book I read years ago that tells the history of the Salinas Valley from the perspective of its eponymous underground river, the longest in North America. It was certainly never a river I thought about swimming in, and the idea that somebody might do just that always seemed suspect and fairly disgusting, though I knew Steinbeck did as a child, as my copy of A Journey into Steinbeck’s California confirms with a picture of Steinbeck and his friend Glenn Graves nude by the river and an uncited quote by the Nobel Prize-winning author:

And then the summer came, and the water in the Salinas River went down until there were only pools against the bank. The Salinas River is three miles from Salinas. We could walk to it or ride bicycles to it. Mary and I rode Jill. We strung ropes to the saddle horn and the pony pulled lines of bicycles to the river. Then, of course, we went swimming.

To me this is insane, and not just because of the perpetually chocolate-brown muddy character of the river when it does run: it is so heavily drained by the Salad Bowl of the World (a moniker that gives the local NBC affiliate KSBW) that in recent memory ocean water was sucked into the river via the lagoon where it empties into the Monterey Bay due to drawing too heavily on the subterranean stream; and because the massive conglomerates make no effort to hide the abundant use of pesticides throughout the valley, meaning that, when the river passes by Salinas City (three miles to the west) it has picked up 100+ miles of industrial-ag chemical run-off. Such is the infinite appeal of the past…

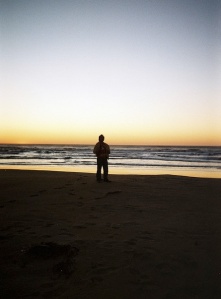

On my next day off I resolved to ride my bike down Portola Drive to the river to see for myself what California State Historic Landmark 560 was all about. I knew in concept that we as a people were helplessly disconnected from the land and its features, but I never realized how literal, in this case, this disconnection was—I spent my whole life crossing the river two stories in the air on a nondescript block of asphalt-topped concrete, viewing it at 65 miles an hour out the car window as on television, a documentary on Steinbeck, for example, the role of the river in his writing, the original motif for East of Eden, its above/underground nature as metaphor for the duality of human nature, as it existed, for him, when it meant something to somebody. I didn’t see the river as a-person-standing-at-its-shore (I didn’t stand at its shore) and really see it until the age of 23 when I went to the Salinas River National Wildlife Refuge, another anomaly at the end of a dirt road that looks like an agricultural-access extension of Del Monte Avenue—the longest road on the Monterey Peninsula that gained its name from the Del Monte Hotel that gave way to the post-Mexican era of sleepy Monterey and made way for its bright future as Mecca for tourism, connecting downtown Monterey with the old Del Monte Hotel, and thus the 17-mile drive laid out for its patrons, and meandering along the bay all the way to the Salinas River a dozen miles out of town.

I found these photos on the internet (my friend’s flickr) of that fateful reunion with the river I never got to meet:

The trail meanders along the lagoon’s edge and then over the dunes that separate the valley from the bay, and on to the beach just south of the mouth of the river where the lagoon empties into the Pacific.

I had just bought a red sweatshirt at the thrift store adjacent to the Marina dump with a huge Mickey Mouse® decal on the front. It was on a mannequin and I was allowed to purchase it right from its back. It was a good day.

I therefore was open to the possibility that a miraculous experience awaited me as rode my bike along Portola Drive, the road parallel to and between the El Toro Creek—not even subterranean as much as perpetually dry—and Highway 68. I crossed Reservation Road, which becomes River Road on the other side of 68 and follows the Salinas River all the way to Mission Soledad, and saw that the small stretch of road that continues was no longer Portola Drive but—pause for dramatic effect—Hilltown Road. It’s real! Hilltown exists!

I took several pictures and walked around and saw absolutely nobody, which was eery considering there was an unaccompanied tractor audibly running.

At the end of the road there was no indication that a ferry once transported early Californian pioneers across the river, nor was there anywhere for someone to approach the riverbed. There was rubble, overgrowth and prohibitive signage; and a most unorthodox breakroom (worker’s rights postings and portable toilet), though one appropriate to fieldwork, I suppose.

I climbed on top of the pile of bricks and dirt at the end of the road but the weeds and thickets quickly became too thick to pass so that I couldn’t even see the riverbed much less a feasible passageway, and I worried I was already trespassing, not partaking of the riches of my people’s historical interaction with the land as I had hoped.

I got back on my bike and pedaled the only direction that seemed open to me: back where I came from, crossing back across Reservation Road and back onto Portola Drive, past the building whose sidewalk bike rack I had left my bike against a few days before, and I thought about the meaning of all of this, the romantic luddite voice echoing through my mind:

This world would be so much better if all of these commuters blowing overhead at 70 miles an hour had to stop, realize there was a river and put value on its crossing, even if it is a quarter flipped to the operator, interact with a man who spends his day ferrying folks across, forced to put their feet on the ground, smell the wildflowers, and hear the gentle babble of the waterway that sustains and defines us.

Even if there wasn’t any institutional acknowledgment of the Hilltown Ferry Historic Landmark, I would, in a better world, be able to park my bike in front of a corner store, buy a soda and ask the proprietor about Old Hilltown, but no, just the aforementioned, kafkaesque building—with a full parking lot at this point—downtown headquarters for a place that doesn’t exist, designed by an architect who doesn’t know his plans would build this building, though, more likely, an architect was never even consulted in this infinitely reproducible, artless edifice.

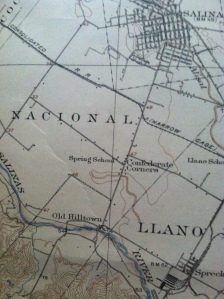

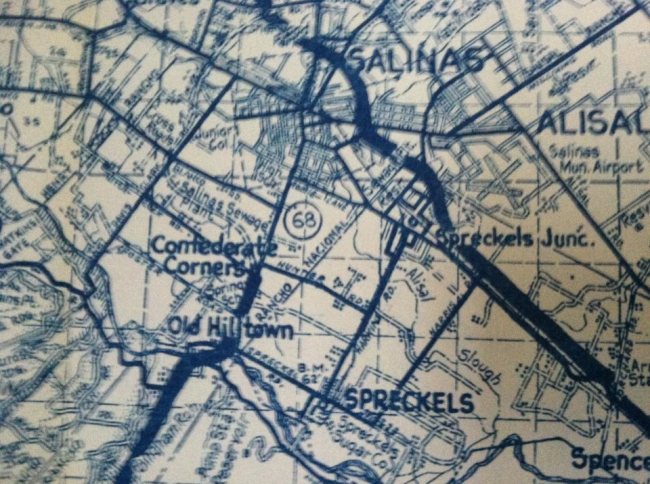

When I got back to the house I looked at my 1912 Department of the Interior map of the “Salinas Quadrangle,” and there was Hilltown:

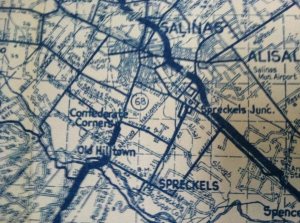

or, as my later 1970s Metsker’s map calls it, Old Hilltown:

And then I went back to the California State Park’s Office of Historic Preservation’s page again and read the location they gave:

Location: On Old Hwy 68, SW corner of Spreckels Blvd and Old Hwy 68 (P.M. 18.1), 3.0 mi SW of Salinas

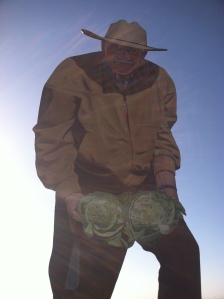

It was on the other side of the river, where I would have theoretically seen Steinbeck and his friends pull up behind his pony if I were meeting them at the river in my imagination, as I kind of was. The vague green patch of historicity I saw on google maps was accessible from the east side of the river, where de Anza would have first approached it as well. It was now rush hour and approaching the evening, and I was not ready to take the Bridge of Death for the first time on bike, instead borrowing my mom’s car, getting on 68 and taking the first exit after the river, Spreckels Blvd. Even though I didn’t know what “Old 68” was, I figured it couldn’t be too far from “new” 68, i.e. present 68. However, when I arrived at the intersection on the west side of the freeway overpass where Spreckels Blvd. presently terminates (though I don’t think it historically went under an overpass), all I found was more NO TRESPASSING warnings at the beginnings of dirt farm access roads, the freeway onramp, and the locally infamous wooden cut-out 30-foot mural of an older farmer very proud of two massive heads of cabbage:

and a similar view of the riverbed, though, of course, from the other direction:

I drove back home in my mom’s car and looked down at the river with a face of scrunched inquiry as I drove over it, and returned to the internet, which seemed to give more answers about the patch of land and water it described than the physical place itself could yield. It was a confusing intersection, after all—Highway 68, an east/west commuter corridor, runs north/south at the moment it crosses the Salinas River, a north-flowing subterranean river that, at the moment it goes under the highway, goes directly west, and visibly contains superterranean water. It is a freeway for a brief 3-mile period beginning just east (north) of the river, but the plan was scrapped soon afterward the bridge’s construction (and an overpass above Market Street in Salinas five miles away), and the highway ends shortly after it begins. It is part of the Historic Juan Bautista de Anza Trail that begins in Sonora, Mexico and ends in San Francisco—the present-day 68 bit is the only doubling back of the whole trail, taken to connect Monterey (“discovered” by sea) with the newly explored land-based dot-connecting—but none of the 26,000 commuters that drive on the 16,000-capacity rode give a shit, especially not at the bottleneck a couple miles from the river where the freeway becomes a two-lane highway. It was an historically passable natural ford in the river and is the only present way to cross the river for the civilization-inclined.

Before we go any further allow me to answer some questions with the great boon of my internet research, an article by Robert B. Johnston circa 1958—around the time, I’ve gathered, that the site was determined an Historic Landmark—and donated to the Monterey County Historical Society, published in their July 2003 newsletter (available in .pdf), which begins with an update on the building’s renovations, a building of which, like the society and the newsletter (living here nearly my whole life as a Monterey County history enthusiast), I have never heard:

What and where is Hilltown? At the point where the Monterey Highway (the extension of Salinas’ South Main Street) curves to the right for a few hundred yards before crossing the steel bridge, a general store and motel stand on the site of a very small community that has existed for slightly over a hundred years, serving the traveler crossing the Salinas River on his way to Monterey. Hilltown itself is located near the southeast corner of Rancho Nacional. Directly across the river is the northeast corner of Rancho del Toro. This rancho extended in a southwesterly direction up the little valley of El Toro Creek, which flows between low hills at the foot of a mountain of the same name. Hilltown almost marks a corner common to four ranchos established along the Salinas under Spain and Mexico—Buena Vista and Llano de Buena Vista joining El Toro and Nacional along their eastern boundaries. No doubt even before the first white man came to the valley, the Indian hunter crossed at this natural fording place. It was been known successively as El Paso del Quinto, Estrada Crossing (after one of the rancheros), Salinas-Monterey Crossing, Hilltown (after one of the first American farmers to locate here [J.B. Hill, eventual postmaster for tiny Hilltown]), and Riverside. The earliest Spanish explorers followed the Salinas River along the bank opposite Hilltown by a route which hugs the feet of the Santa Lucia Mountains from Soledad to its junction with the crossing at Hilltown. This is the River Road of today.

It included some great pictures:

This article was like a pebble dropped in a pool, the center of a series of radiating ripples of time that extend infinitely in each direction on either side of it, and I saw history refracted through the centuries and my own perspective fading off in one direction as the past and our perspective on it float uncertainly as I float away from it.

When Robert B. Johnston wrote about the crossing, the latter-20th-century concrete, freeway monstrosity had yet to replace the 1889 truss bridge, and the eldest members of the community could recall the crossing, or stories of it, distant and shadowy memories. The appeal of California history is its accessibility. Things changed so drastically and quickly every generation since the Spanish first arrived, and each wave of immigrants that succeeded them, that ancient history—that is a radically different societal character—exists within a century. More has changed since Johnston wrote about Hilltown than changed between the ferry’s was discontinuance in 1889 and the 1958 article.

When Steinbeck returned to Monterey County in the early ’60s he hardly recognized his hometown. It had ballooned to 19,000, more than double the size of the town the young writer had left in the ’30s. At the turn of the millennium the population peaked with the tech boom at 150,000, where it remains today. If Steinbeck found Salinas unrecognizable after the town doubled in size, seeing it sprawl to ten times its former existence must convince one it does not resemble nor is it the same place.

As in most of California, the last fifty years have made the post-Gold Rush century—and the Spanish and Mexican century of settlement that preceded it—statistically meaningless. The new pioneers were Walt Disney in Anaheim, settling the now famous site of Disneyland in 1955, the California Department of Transportation all across the state, creating mind-boggling freeway webs and “stack interchanges” that I first encountered in cartoons including the world’s first in 1949 (opened in 1953) in the Bill Keene Memorial Interchange in LA where the 101 meets the 110. Thomas Kinkade was born in 1958. Ronald Reagan became a Republican in 1962 and the Governor of California in 1967. Arnold Schwarzenegger, age 21, moved to Venice Beach in LA in 1968.

Malvina Reynolds, born in San Francisco in 1900, long enough ago to remember pre-Disney California, drove through SF’s suburb to the south, Daly City (a similar story to Salinas, literally peripheral to history until the post WWII boom, 1950: 15,191; 1960: 44,791; presently over 100,000), one day in the ’60s and she saw this sprawling mass of “Little Boxes,” as she famously called them, housing tracts that she didn’t even know were there, having lived in the Bay area her whole life; but, in the words of her daughter, when she was asked years later to point at them for a magazine photo op, “she couldn’t find those houses because so many more had been built around them that the hillsides were totally covered.” They are all made out of ticky-tacky, after all, and they all look just same, so how can one point out the first ones?

The new pioneers paved acres of parking lot around anything they built, malls and then strip malls and then big box stores, the bigger the building the bigger the concentric surrounding white-lined asphalt, further and further from the city centers which shriveled and dilapidated as the money and people abandoned them. This is the ripple we have ridden since Robert B. Johnston wrote about Hilltown Ferry, the one he turned his back on as he considered the ripples of the previous centuries as they pushed away from him in the other direction. 1958 is also the year of the Nacimiento Dam’s dedication, which marked the end of the Salinas River’s wild run through the valley, the beginning (nacimiento means “birth”) of ten years of construction that ended in the completion of a second damn/reservoir/”lake” in 1967 with the birth of Lake San Antonio. The “part-time” river became a full-time trickle, not the ebb and flow that informed Nobel Prize-winning authors of the cyclical nature of reality and the existence of seasons, that, when the summer came, and the water in the Salinas River went down until there were only pools against the bank. you could walk to it or ride bicycles to it, you strung ropes to the saddle horn and the pony pulled lines of bicycles to the river. Then, of course, you went swimming.

Post-WWII California was not a place of truss bridges and occasional floods, uncertainties, history. Of course there had to have been an elegant, historical truss bridge that crossed the Salinas, though the fact never occurred to me—though I’m having a damn hard time finding a picture—all I had to do was think a few miles downriver where Highway 1 (a four-lane freeway just north of Marina) crosses the Salinas River along with an old steel bridge still standing and in use right next to it, which, when I am not in a hurry, I will take, avoiding the freeway and ambling 25 miles an hour, glancing down into the river as it opens up just before flowing into the bay. The last sixty years have spared this bridge, along with certain other fragments of history, either ignored by the new pioneers or embraced and promoted. I love and appreciate the California State Park system—mostly for the preservation of the land, buildings and monuments that they preserve/are—because they take profit out of sightseeing. However, just as places remain as they were to the extent that they continue to profit as such, restoration and maintenance of the past is directly related to the public interest, and the park closures of the last year in California directly illustrate this dire situation. Anything that was labeled and saved before the new pioneers—Monterey’s incredible Walk of History and series of intact adobes, gardens and, Custom House Plaza (NO. 1!)—becomes a classy and educational version of Disneyland; anything that was not, yet still brings a tourist pull—New Monterey’s bayfront now-tourist neighborhood named for Steinbeck’s Cannery Row whose “central theme,” in the words of Erik Enno Tamm, Edward Ricketts’ biographer, is actually a rejection of this type of mindless materialism, and instead a celebration of the spiritual and the marginal in society,”—loses integrity to mass-marketable kitsch (just as Disneyland loses more integrity ever year as it caters to the tastes of 6 year olds, when it should be an historic landmark), which, in the case of “Cannery Row,” still in Tamm’s words, “must be one of the most ironic, if not tragic, footnotes in American literary history”; anything that received acknowledgment past the era of the new pioneers and has no inherent or constructed tourist draw—Hill Town Ferry was registered the last day of 1956 and is an overgrown riverbed underneath a freeway—fades away to the forces of new pioneer capitalism, it exists on maps, in theory, but is inaccessible to those who don’t seek these means of interpretation.

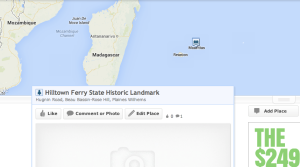

During one of many google searches I found that Hilltown Ferry State Historic Landmark had a facebook page. I was the first to “like” it, and was the first to “be there,” that is, on the facebook page, one that seemed to be generated by a kind of facebook-page-generating robot that takes landmarks off of google maps (facebook actually works with bing…) and lets other people fill in the information, which no one had. It was in Salinas, it was 68 degrees (another robot-generated fact), it exists in an indeterminate category with unspecified hours. I gave it five stars and explained why the place had become so dear to me: “It no longer seems to exist but the internet and California State Parks seem to insist that it does.”

Another google search a few days later changed everything. Someone rated Hilltown Ferry State Historic Landmark on google+ and shared his experience—someone I did not know became so curious in the last week about this place he went there just as I did, but he went there and found it. This is what he wrote:

You do not want to go here. From the end of Hilltown road, you can get to the site of the Hill Town Ferry only by pushing through extremely dense underbrush of waist-high vines and poison ivy. I know, I found it and have the poison ivy to prove it! There is no trail at all, not even a game trail and the place is full of ticks. When I left, I followed the river towards Highway 68 and had to exit on private property. All in all, not much fun.

So that was it. The truth could be found, but it was not much fun. The California of the mind is always richer than whatever existed and continues to exist underneath these lawns and acres of concrete. There was a picture uploaded of the remnants of the ferry, but the post on google+ has been deleted, though it still reverberates through the internet, presently the text copied above is on walkscore.com which thinks Hilltown Ferry State Historic Landmark is a park in Beau Bassin-Rose Hill, a town on the west end of the tiny island of Mauritius, a hundred miles or so east of Madagascar.

I am taking screenshots because the non-existence of Hill Town Ferry will continue to ripple through robotic page generations on the internet. It won’t be in Beau Bassin-Rose Hill on Mauritius forever, just as it wasn’t a crossing of the Salinas forever. The new pioneers push history into exhibits, informational signage and wax museums, and whatever doesn’t fit slips off into nothingness, like the stream of a subterranean river flowing to the bay.

Andrew:

I will dig around to see if I have the pictures I took of the Ferry cable support structure.

Tony:

Please do! When were they taken?

I found only 1 pic and re-uploaded it to my Google Plus review. It is from May 8, 2013. You should be able to find it now. The structure is exactly where Google Maps shows the marker.

As an FYI, I have been discussing it with someone I know who grew up in Salinas and he thinks Google Maps is somehow completely wrong about the location. Personally, I have trouble believing that because if it wasn’t state land it would have been leveled and plowed like the surrounding fields. Google maps also seems to be extremely accurate with property lines.

I found your review and I realize I referenced it when I wrote this two years ago! So there is a structure at the end of hilltown road, past all of the brush west of 68 in the river? Thanks for uploading that and helping to solve the mystery!

I’m 65 years old and remember Old Hilltown. My dad would stop there on the way to Salinas and have a beer at the bar of the Hotel. Old Hilltown was at the intersection of Spreckels Blvd and Highway 68. The ferry was located at Hilltown straight in line with Hwy 68 as you would approach it from Salinas to Monterey. The road marked “Hilltown” on the West side of the river is the old hwy 68 crossing. The old two-lane steel Salinas River bridge was located there, I used to drive on it. Old foundation piers for a still-older bridge were visible upstream when on the bridge.

When traveling from Monterey, River Road intersected hwy 68 right at the bridge, you would then cross the bridge, & make a right hand curve south, to Hilltown, then make a left curve to head to Salinas. There was a two story Hilltown hotel at the intersection of 68 and Spreckels Blvd, (marked “Spreckels lane” now). It was torn down when the new bridge was constructed but the site is still there near the historical marker, end of Spreckels Lane. The Google Maps marker location was wrong but I submitted a correction and it is fixed now. Across from the Hotel on the left side of the road (heading towards Salinas) is were the “Del Rio Appartments” Those were moved to 319 Hitchkock rd. The Hill family had a large house on main street salinas, near the current Wells Fargo Bank. It was moved to make room for the bank. The house was transported to the Gould Ranch, which is now Wild Things animal park at the corner of Pine Cyn Rd/River Rd. It was cut in half to transport, then re-assembled by Phil Gould who owned that property in the 70’s. Phil worked for Monterey County road dept. I’ve had interest in the type and number of bridges in that area over the years and the Coalinga crude oil pipeline which had a pumping/heating station off “Hilltown rd” The empty lot used for pumpkin sales is the site and it was paved over to prevent oil contamination from moving. A lot of work was done there in the late 70’s to clean it up, digging a big hole, pumping shallow ground water into tanks and hauling it off.

Hi Andrew, this may be a couple of years late, but like the response posted by David, I too am in ny 60’s and remember the old bridge, 1889-1967. I too recall exactly where everything was and in reading your article, it doesn’t sound like you found the historical landmark marker. I can help you find it as well. Ny dad also used to stop st the roadhouse which used to be located where they sell pumpkins every year. Anyway, thanks for the article and let me know if you need help.

I posted some photos of the Hilltown Historical marker on The Old Hilltown Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/pages/Old-Hilltown-California/109878099031688